History

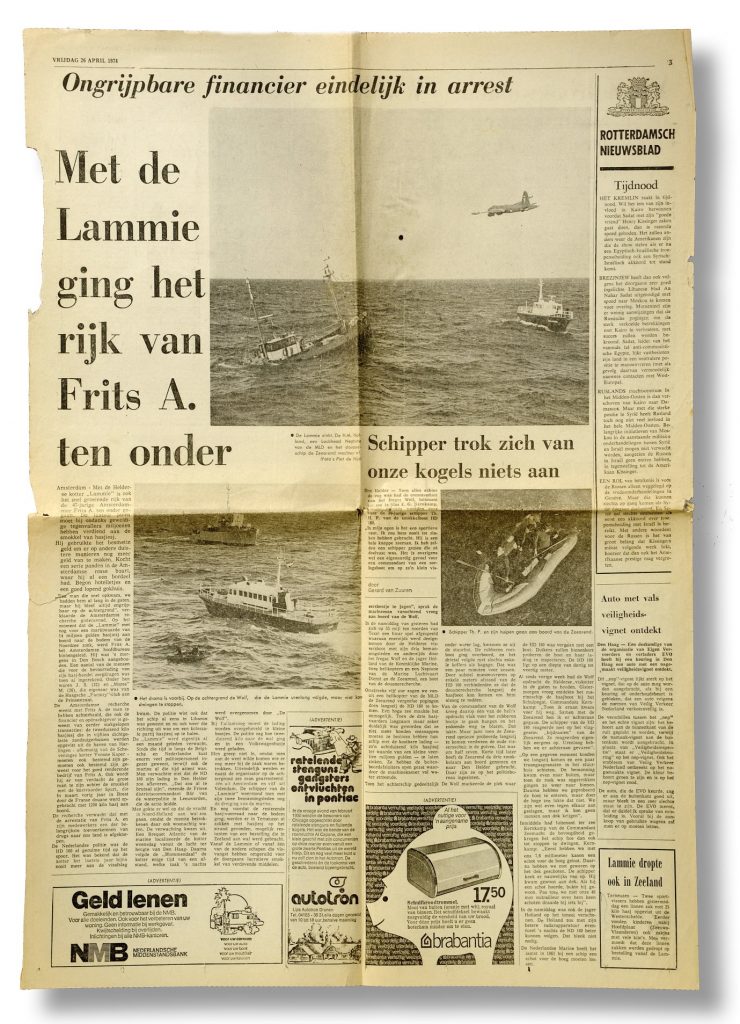

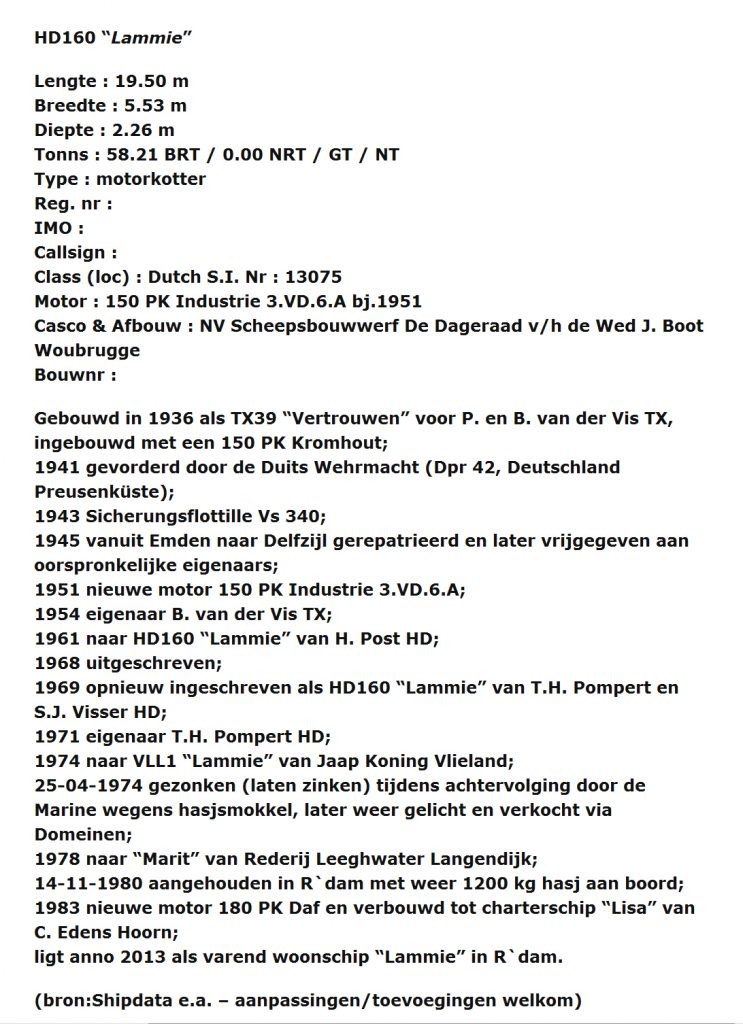

HD 160 – the Lammie – is a boat with a colourful past. This unassuming little vessel became the focus of national media attention in April 1974, when it became a symbol of the fight against organised crime in the Netherlands and the cat-and-mouse chase that preceded the ship’s sinking has entered Dutch folklore.

Read the full story:

In the 1970’s, Amsterdam was beginning to achieve a certain notoriety as the city of free-thinking, free-love, sex, drugs and prostitution although for centuries it had always been a city where people were free to pursue their own interests – as long as they didn’t bother anyone else. The Wallen – commonly known as the Red-light District was a warren of bars, clubs, sex-shops and theatres that were run by louche, mafia-like figures with names like Frits van de Wereld and Zwarte Jopie. It was by-and-large a self-regulating world and the police seldom ventured into it. If someone pulled a knife in a bar-fight his fingers would be broken – a kind of gentleman’s agreement that stopped things getting out of hand. However, the advent of cheap jet travel in the 1970s meant that tourist traffic was increasing. The fleshpots and coffee-shops selling not coffee, but hash, were popping up all over the place and becoming more and more of a tourist attraction.

Smuggling in some of the small fishing ports along the north Dutch coast was nothing unusual, mostly cigarettes and alcohol and the likes, and a pretty penny could be made. Frits van de Wereld decided to finance a hash-run to bring home some supplies for his various establishments in the Wallen. He, and a few other scurrilous ‘investors’ stumped up the cash to finance a large-scale hash deal with a secret supplier in the Lebanon and set up a deal with the owner of the HD 160 to sail all the way there and bring back the illegal cargo.

Unbeknownst to Frits and his partners, the authorities had been keeping an eye on the Lammie as it had been spotted by Interpol in the latter half of 1973 near the coast in the Lebanon. This earlier hash-run was a disaster. The Lammie was discovered sailing without lights just off the coast and boarded by Israeli Special Forces who thought it was an espionage vessel trying to sabotage nearby peace-talks. The Lammie sped back to the Netherlands with an empty hold. The police in the Netherlands had just started using phone-taps – a new high-tech weapon in their fight against crime. They soon got wind of the new hash-transport deal going down and decided to make an example of the Lammie and to show the criminals, who was the boss. The authorities hatched a master plan to monitor and track the boat all the way to the Lebanon and back and to pounce at the moment when the illicit cargo was handed over. An elaborate scheme was set up between the Maritime Police, Customs and Excise and the Navy and a plan of action was drawn up, covering every detail and eventuality that might occur.

As the Lammie sailed out of Den Helder in February on the long trip to the Mediterranean, customs officer Arie Dekker, watching the boat depart, thought to himself that it would be more honest to arrest the unassuming crew and say: “We know everything lads – the game’s up.” In the small fishing communities of Volendam and Den Helder everybody tended to know everybody else – the good, the bad and the ugly.

After an eventful voyage in which the Lammie picked up it’s cargo of around 4,000 kilos of hash in the Lebanon and shortly thereafter almost sank after getting caught up in a hurricane off the coast of Cyprus, the ship finally entered the English Channel on 24th April. Every lighthouse and harbour, large and small, along the Belgian and Dutch coasts was manned with Customs officials, as the authorities had no definite idea where the drugs would be landed. The Dutch Navy corvette H.M. de Wolf picked the Lammie up on her radar and began shadowing her from a discrete distance of around 10km. The English Channel has some of the busiest sea-lanes in the world and sure enough, in the darkness of the night, the contact was lost. The air onboard the bridge of the Wolf was blue with swearing, however, the little boat was picked up again and the shadowing continued. The net began to close around the Lammie. She passed the coast of Zeeland and cruised slowly along the coast and passed Ijmuiden eventually slowing by Calantsoog and came to a stop directly in-line with an onshore radar-post. A rubber motorboat was lowered into the water and the first part of the illegal cargo was brought ashore. The authorities, whom had virtually sealed of the entire North-Holland, had already spotted a couple of Volkswagen vans and a couple of cars waiting near the beach path. They let the shore-based accomplices load up the vehicles with 2000 kilos of hash and depart, whilst the rubber boat made it’s way back to the Lammie. The main target was not the drugs themselves, or the middlemen from Volendam, but the ‘masterminds’ – financiers Frits van de Wereld and Mooie Willem. Most of the accomplices were arrested on the beach. The vans were followed and took their loot to a warehouse in the small fishing village of Volendam where, after a shoot-out the ‘logistics’ bosses were arrested. One of the cars was followed all the way to the province of Brabant in the south of Holland. The car was a cream Mercedes containing Frits and his partner Blond Greetje who was making a personal delivery to an accomplice. Frits was dropped off at a curve in the road and Blond Greetje drove to a barn, which was to be used as a secret stash. At 08.30, the Police pounced and found 51 kilos of hash in the boot of the Mercedes. Frits was later arrested at the house of the accomplice as they sat drinking coffee.

Time to swoop

The task now for the authorities was to grab the Lammie and the rest of the drugs and then they would have all the evidence they needed to make the big splash in the media. They decided to swoop and called-in a veritable arsenal consisting of a Neptune aircraft, an Agusta-Bell helicopter, the customs boat Zeearend and the submarine-hunter the Holland. It was now the morning of the 25th of April and the sea was rough.

Despite requests by both the Customs and Navy to stop, the Lammie continued her course, full-steam ahead north. The decision was taken to fire warning shots across the bow of the Lammie – an internationally acknowledged warning signal. The shots thwacked into the sea a few hundred metres in font of the Lammie, but she did not alter her course or reduce speed. The order was given to fire tear-gas grenades into the wheelhouse. Aboard HM de Wolf was a team of Marines – sharpshooters. Their first tear-gas grenades went in one side of the wheelhouse and out through the other. The captain, Dorus Pompert, later claimed that the third grenade shot his coffee-mug out of his hand and left him holding only the handle.

The sharpshooters, by increasing the angle that they were shooting from, managed to get some grenades onto the deck and into the hut, but the crew ran out and threw them overboard. Also, the hard wind blew the gas quickly away. This strategy obviously wasn’t working, so the decision was taken to ram the Lammie. HM de Wolf set a collision course and whacked the bow of the Lammie, making a large dent in the prow, but to no effect. Captain Dorus Pompert and his crew were having nothing to do with it. “Stand back” they warned, “We are about to commence fishing.” The fact that all the fishing gear had been removed prior to departure for the Mediterranean was apparently irrelevant.

Open Fire!

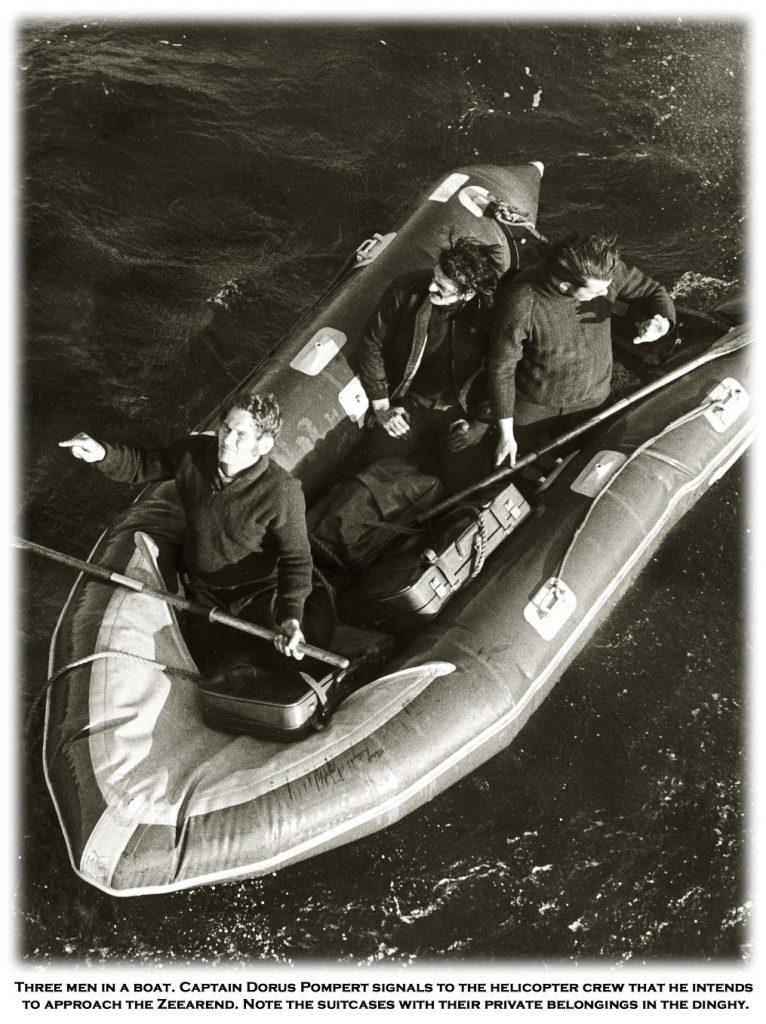

The Lammie continued on its course northwards and refused to take heed of the warnings. The action escalated. The turret guns onboard the Wolf were trained on the Lammie and shots were fired with a 40mm canon at the crew quarters and engine room in an attempt to hit the ship’s engine. Pompert emerged from the wheelhouse and, pointing to his chest shouted to the authorities: “If you shoot, you’d better aim here.” The orders were to spare lives but to grab the hash. The canon-fire ravaged parts of the deck and one shot struck the engine and disabled it. Realising that the game was finally up, the crew dived below decks and they opened the outboard water-cocks for cooling the engine and, unbeknownst to the authorities, the Lammie slowly began to sink. The crew came back up top, tied the ship’s-wheel fast so that the boat would sail in circles, loaded their cases with personal possessions into the rubber boat and nonchalantly rowed away from the sinking boat. The authorities were furious. The Lammie had slipped out of their grasp. There was, for a moment, a plan to board the sinking vessel to try and halt it going down but it was deemed too dangerous due to debris being trailed by the boat and by the rough sea. Concerned that the authorities might attempt this, as the boat was sinking slower than expected, the crew attempted to row back to the Lammie and get onboard to make sure she went down. The helicopter, which made a total of three round-trips that day and which had been flying around the scene allowing the media onboard to photograph the action, flew down close to the rubber boat and used the downwash from the rotors to blow the boat away.

The crew needn’t have worried. The Lammie slipped stern-first under the waves and disappeared from view. The customs boat Zeearend picked up Pompert and his crew and by all accounts things were on an entirely amicable footing. It is said that the crew enjoyed a cup of coffee with the Customs men in the galley, and that Pompert was complimented on his seamanship.

Chicken-feed

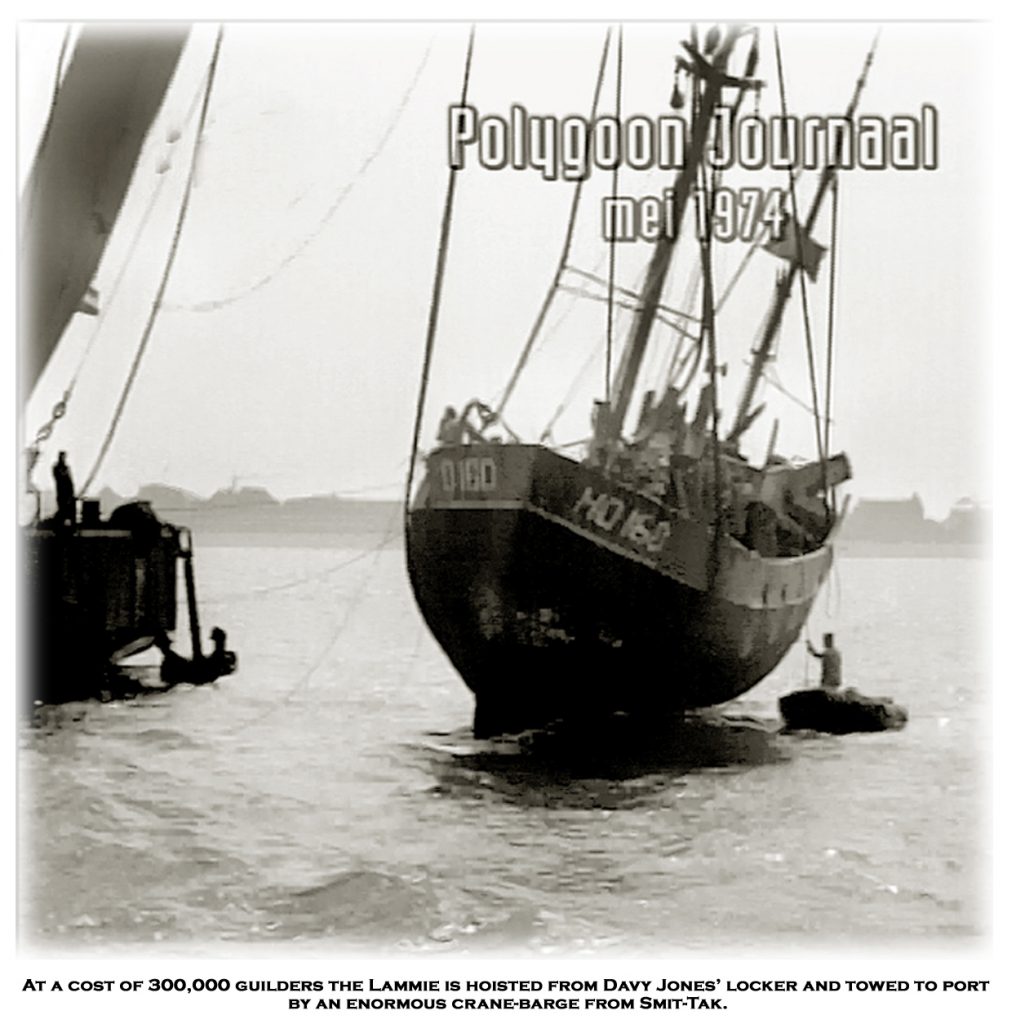

But the story doesn’t end there. Not just yet. The Lammie had sunk in a mere 44m of water. In addition to the bales of hash onboard, Pompert later divulged that there were also around 27 rubber hot-water bottles containing around 40 litres of hash oil (one litre of hash oil was good for 1,000 kilos of joints). Later rumours hinted that the oil was most likely destined for the US market, as it was a relatively unknown commodity in Europe at that time. The authorities feared that the criminals would try and salvage the cargo and so the decision was taken in the following days to raise the Lammie. A large floating-crane from Smit-Tak was brought in, at a cost of around around 300,000 guilders, and the Lammie was raised from the seabed and towed into the harbour at Den Helder on the 3rd of May. Customs officers leapt onboard and found below decks the bales of hash, packed in sacks labelled as chicken feed. Also, under some netting, they found the hot water bottles.

The loot was taken to a nearby incinerator and destroyed. The boat was declared a wreck and put up for sale by the State. After receiving compliments from the judge on his seamanship Dorus Pompert and his two crewmembers received prison sentences of 12 months. The ‘masterminds’ Frits van de Wereld and Mooie Willem, after lodging objections against a four-year sentence, finally received 19 months each – symbolic of the ‘relaxed’ approach that the Netherlands took to soft drugs at the time. In neighbouring countries the sentence for drug trafficking was around 12 years.

The Lammie’s new owners were obviously impressed at the little vessel’s potential and after a refit and a name-change to the ‘Marit’, the little boat was once again up to no good and was intercepted in Rotterdam on Friday 14th of November 1975, carrying a cargo of 1,200 kilos of hash.

Footnote: As a result of ‘Operation Lammie’ – which involved intense cooperation between Customs, Navy, and Police, the Dutch Coastguard was brought into existence in order to provide a more-effective, single force for defending the sea-frontier.

A longer, more detailed article describing the swashbuckling story of the Lammie in full is currently in production and will be posted here once completed.